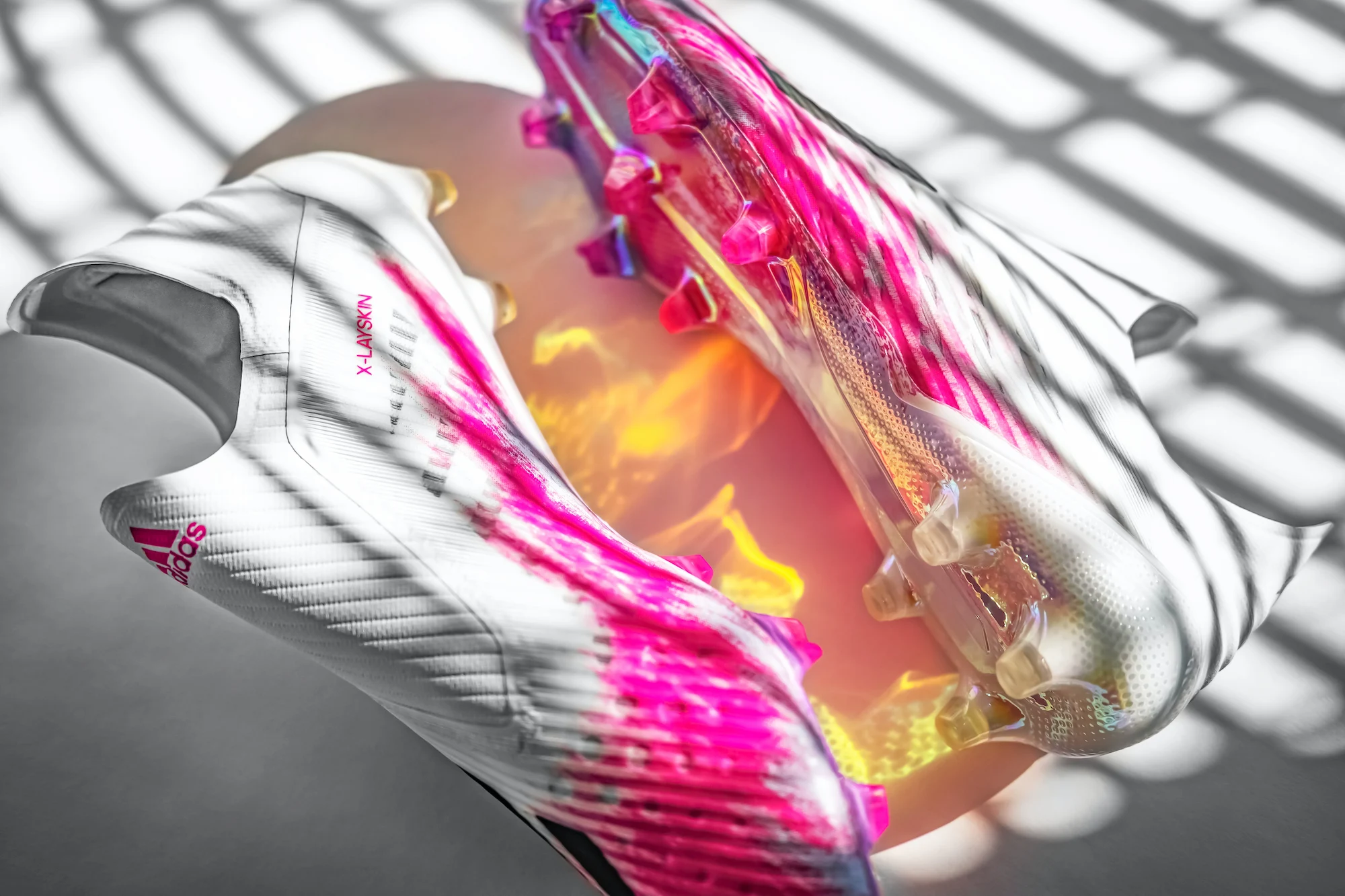

Have you ever wondered why football boots are called boots? Made from synthetic materials to be feather-weight and available in every conceivable colour, the footwear on display in the Premier League today bears little resemblance to a traditional boot. But that wasn’t always the case.

Back in the final decades of the 1800s, when football was taking its first steps toward professionalism in the north of England, most players came from working-class backgrounds. They would often be employed in coal mines, shipbuilding yards or factories. The boots they would wear to work would be heavy — made from stiff leather with steel toe-caps to be long-lasting — and offer protection to their feet. It was these black or brown ‘work’ boots — with primitive studs nailed into the soles to give some grip on muddy pitches — that they would use to play football.

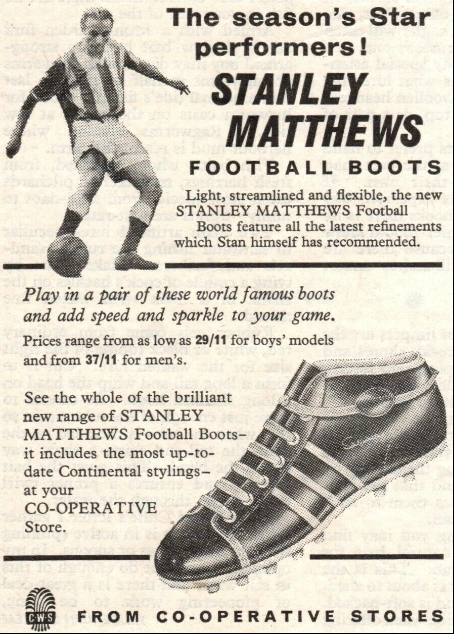

While the popularity of professional football began booming across Britain after the Second World War, there were few advancements in boot design or technology. The greatest English player of the time was Stanley Matthews. Known as ‘the wizard of the dribble’ for his mesmeric ball control and ability to twist and turn his way past full-backs, Matthews played on the right-wing for Blackpool and England. By the time England travelled to Brazil for the 1950 World Cup, Matthews, by then aged 35, was considered a veteran, close to the end of his career. England endured a torrid time in South America – losing infamously to the USA (a team comprised of amateur players) and Spain — and were eliminated in the opening group stage.

Rather than flying straight home, Matthews decided to stay on and watch the rest of the tournament. He took a particular interest in the Brazilians. Wearing white shirts, rather than the yellow ones they are now famed for, Brazil were heavy favourites to win their first World Cup. Before the final game with Uruguay, in which the hosts only needed a draw to clinch the Jules Rimet trophy, the Governor of Rio declared the team to be “without equals” and already “victors of the tournament.” Uruguay were having none of it. Coming from behind in the second half, they won 2-1 and claimed their second World Cup crown. While the Brazilian public was devastated by the result, Matthews took something from the match that would transform the game in Europe. He’d noticed the Brazilian players — admired for the high-speed attacking play — didn’t wear boots like him. Instead, they wore light-weight shoes cut below the ankle. Matthews was convinced this, combined with their exceptional ball skills, enabled the Brazilians to play the game with such beauty.

As soon as Matthews returned to England, he took a sample of a Brazilian boot to the co-op. He tasked them with producing a prototype for him to wear in the 1950/51 season. When Matthews first wore his new ‘Brazilian-style’ boots to training, his teammates and manager were sceptical. Opposition players would openly mock him for looking different to everyone else and stamp on his feet. Matthews paid little attention.

In 1953, Stanley Matthews, aged 38, was the man of the match as Blackpool beat Bolton 4-3 to win the most famous FA Cup final ever played at Wembley. In 1956, aged 41, he was named the first-ever winner of the Ballon d’Or. He would win his last cap for England in 1957 at the age of 42 and would play his final match in the top flight of English football in 1965, a few days after his 50th birthday.

By then, everyone in Europe was wearing the new style of boot he’d first seen in Brazil. By the start of the 1954 World Cup, Adidas had taken the design a step further. Their innovation — which allowed different length studs to be screwed into the sole of the boot — enabled the West German team to conquer Hungary in a rain-soaked final.

Today, the football boot industry is estimated to be worth over £3 billion globally. But for Stanley Matthews’s ‘growth mindset’ and willingness to embrace rebel ideas, who knows what the players taking to the field in the 2022 World Cup final might have had on their feet? It’s a story we love to share with our young people on the Behind Every Kick Development programme.